In June of 2017, Mount San Antonio College, a community college in the Los Angeles suburb of Walnut, California, was awarded the prestigious 2020 United States Olympic track and field trials.

For Olympic organizing committee chairperson Bob Seagren, this was a major coup for his alma mater, and the beginning of a long road ahead.

“It’s going to be a lot of work,” Seagren said. “Putting on an event of that size requires a lot of coordination. We have to raise sponsor revenue, we have to figure out who is going to help us with marketing ticket sales. We have to make sure our (Hilmer Lodge) stadium renovation stays on schedule.

“We want to make sure we put on a great show. We want to make sure we present track and field in the best light we possibly can to the world,” Seagren added. “It’s a great opportunity for us. There’s a lot of revenue on the line.”

And a lot of pressure.

Fortunately, Seagren has a proven track record of thriving when the pressure is ratcheted up.

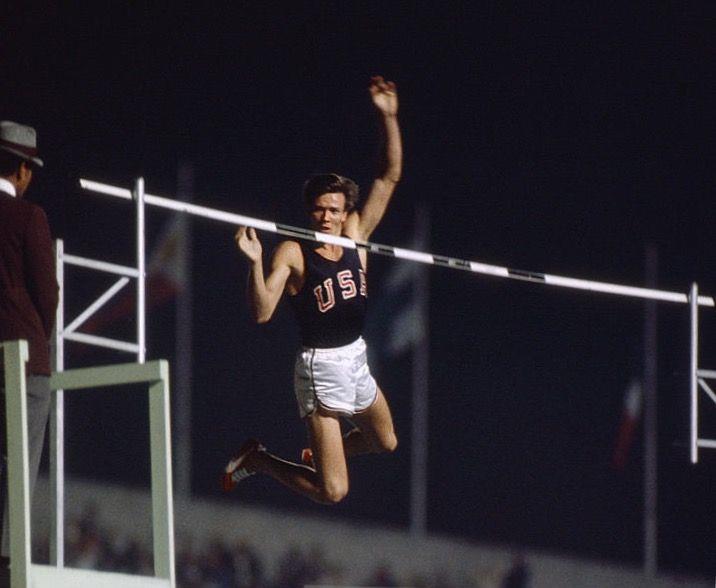

Fifty years ago, during the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, Seagren captured a gold medal in the pole vault with a leap of 17 feet, 8½ inches, breaking Fred Hansen’s Olympic record of 16 feet, 8¾ inches set at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

Seagren had to overcome fierce competition as the medalists, Claus Schiprowski, of West Germany, and Wolfgang Nordwig, of East Germany, all finished the 7½ hour event with the same height cleared as Seagren, but the Pomona, California native prevailed because he recorded fewer overall misses.

Seagren’s gold medal was a remarkable feat considering he was just 21 years old and was competing in his first Olympic games (by comparison, Schiprowski was 25 years old and Nordwig was 24).

“Being my first Olympics, it was quite different than a normal track meet,” Seagren said. “When I got to Mexico City, it had such a different vibe. It really hit me when I walked into the stadium during the opening ceremonies. It was amazing.”

The gold medal was a career highlight of a career filled with highlights. Seagren was one of the world’s top pole vaulters in the late 1960s and early 1970s, winning six National AAU and four NCAA titles indoors and outdoors. He set 15 world records over an 11-year period and was the Pan American Games champion in 1967.

Strangely, Seagren is perhaps best known for the gold medal he didn’t procure, as a last-minute ruling banning the banana-pole from the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich forced some pole vaulters, including Seagren, to compete with different poles than they were accustomed to utilizing. Despite being swept out of his comfort zone at an inopportune time, Seagren still managed to win a silver medal.

“I was shocked because the ruling really had no bearing on the vault,” Seagren said. “A vaulting pole is made based on how tall you are, how fast you can run and how much you weigh. We had to make some adjustments and I ended up vaulting with a pole that I might use in a short-run practice. It put a lot of the competitors at a disadvantage.”

Once his competition concluded, Seagren and his family loaded up a Volkswagen bus and traveled across Europe, visiting such locales as Bavaria, Italy, France and Barcelona. Shortly after he departed though, the Munich Olympics were marred when a Palestinian terrorist group took 11 Israeli Olympic team members hostage and murdered them.

“I left the morning it happened,” Seagren said. “It was three days later I found out what happened. I was getting gas in Northern Italy and the gas station attendant saw the Olympic stickers on my vehicle and was trying to talk to us, but none of us spoke Italian. He started making machine gun noises and explosions and pointing to the Olympic sticker, so we grabbed a newspaper right away to see what happened.”

When Seagren returned to Munich for the Closing Ceremony, the tranquil Olympic village he was accustomed to was transformed into a military state.

“There were police with machine guns everywhere. It was crazy,” Seagren said. “It was night and day from 1968. In Mexico City, my parents walked into the Olympic village to see me whenever they wanted. After (the killings), security was so tight, it was unbelievable. Nineteen sixty-eight was the last of the open free Olympic games.”

After the games concluded, Seagren continued to excel at his craft, winning the inaugural American Superstars sports competition in 1973 and the first World Superstars in 1977. He also displayed his acting chops, as he appeared in several commercials, movies and television shows.

“When I came back from Mexico City after winning the gold medal, I was getting calls from agents and commercial producers and it sounded very exciting,” Seagren said. “The Olympics opened some acting doors for me.”

Over the years, additional doors opened for the Long Beach resident, who went on to become executive vice president of sales and marketing for athletic apparel company PUMA USA before moving on to become CEO of his company RUN Racing, an event management company that owns and operates events and assists race directors.

The biggest event RUN Racing has been affiliated with is the Long Beach Marathon, which the company took over in 2001. Prior to Seagren’s involvement, the marathon had a troubled history, having been postponed in 1981 and taking a three-year hiatus from 1996 to 1998 because of financial issues.

Not much changed at first, as RUN Racing’s first Long Beach Marathon, which took place in November 2001, was immediately hamstrung after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, prevented many runners from competing.

“We had our headaches right from the beginning,” Seagren said. “Obviously, nobody saw 9/11 happening. Our first year, half of the runners didn’t compete because people weren’t flying after 9/11. It was tough, but we tightened our belt. I was on the phone making payment plans to our vendors. You have to hang in there and make it right.”

Seagren did just that and his persistence paid off. Today, the marathon is a considerable success as it attracts around 25,000 participants and brings about $12.5 million to the city from tourism revenue.

“I learned a lot about how to do things better,” Seagren said. “There are a lot of moving parts with the marathon and you’ve got to have good people that can help you organize it. You have to dissect it and break it up into smaller pieces. That was a hard thing for me to learn. I used to try to do everything myself and that almost killed me.”

After years of setting up and promoting events like the Long Beach Marathon and the OC Marathon, Seagren has honed his skills to a fine point, much like he did 50 years ago when he was a precocious youngster poised to compete in front of a worldwide audience. And like then, he has butterflies in his stomach and is inspired about what lies ahead, particularly in regard to the 2020 Olympic trials.

“Everything is a life lesson. You never stop learning and at the end of the day, what I do is rewarding,” Seagren said. “When I think about the planning and preparation that’s going to go into the Olympic trials, I’m excited. Someday I’ll think about retiring, but not today.”