Lesser-known National Park Service locations shine a light on American history and culture, tempting travelers to stray off the beaten path

Virginia abounds with landmarks that tell America’s story from its very beginnings and celebrate who we are as a nation. Many are properties of the National Park Service, with popular examples including Historic Jamestowne and Yorktown Battlefield.

Scattered throughout the state, however, are some overlooked sites with compelling lures of their own. Here is a look at five Virginia National Parks worth a detour: Fort Monroe National Monument

Upon its closure in 2011, America’s third-oldest Army post, acclaimed for its strategic role in defending the Chesapeake Bay, was designated a National Monument. Completed in 1834, Fort Monroe was dubbed the “Gibraltar of the Chesapeake” because of its massive stone fortifications. Located on a peninsula overlooking Hampton Roads, one of the largest natural harbors in the world, this Virginia National Park figures prominently in African American history.

It was at this site in 1619 that the first Africans arrived in English-occupied North America, beginning a period of slavery that lasted for 246 years. And during the Civil War, Fort Monroe became a sanctuary for thousands of escaped slaves, earning it the nickname “Freedom’s Fortress.” (Even though Virginia had seceded from the Union in 1861, the fort stayed in Union hands for the entirety of the war.) Two black regiments formed at Fort Monroe served gallantly in the Siege of Petersburg.

Points of interest on the sprawling grounds include the 1802 Old Point Comfort Light, an active lighthouse maintained by the U.S Coast Guard; the Casemates Museum, a cavern of rooms with Civil War exhibits; the grassy Parade Ground; and Flagstaff Bastion, a hilltop offering views of Hampton Roads. Fort Monroe also offers beaches, picnic areas, nature trails, restaurants and an RV park. (fortmonroe.org, nps.gov/fomr)

Cumberland Gap National Historical Park

This national park, stretching along 20 mountaintop miles where southwestern Virginia meets Kentucky and Tennessee, protects a heavily forested area that looks much as it did when pioneers made their way westward through the Appalachians. From 1775 to 1800, some 300,000 settlers traveled through Cumberland Gap after Daniel Boone and his ax-men cut a trail that became known as the Wilderness Road. The park visitor center has films and exhibits on this important migratory track, a natural doorway through the mountains first used by Native Americans following deer and buffalo trails.

For sweeping views of the gap’s rugged beauty, drive the twisty four-mile road to Pinnacle Overlook, elevation 2,440 feet. On a clear day you can see the three converging states and perhaps even North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia.

The park offers 85 miles of hiking trails and a campground with summer campfire programs. Ranger-led tours are conducted to Gap Cave, full of stalagmites and stalactites, and remote Hensley Settlement, a collection of reconstructed log buildings atop Brush Mountain.

Changing leaves reach their peak in late fall, a popular time to visit the park. In spring and early summer, rhododendron, mountain laurel and other wildflowers, plus blooming dogwood and redbud trees, accent the greenery of majestic oak, magnolia, pine and virgin hemlock that blankets the slopes.

Booker T. Washington National Monument

East of Roanoke, a National Park Service property near Hardy preserves the farm site where a famous African American was born into slavery in 1856. The story of author and educator Booker T. Washington, founder of Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute, is told through a 12-minute video in the visitor center and in living history demonstrations at buildings that replicate those found on a typical 19th century tobacco plantation. On a quarter-mile loop through this Virginia National Park, guests will see pigs in the pen, a demonstration tobacco field and tobacco drying in the barn.

Washington grew up in the kitchen cabin, as his mother was the plantation cook. The family slept on rags on the dirt floor and had little to eat. Washington recalled that they got their meals “like dumb animals get theirs. It was a piece of bread here and a scrap of meat there….a cup of milk at one time and some potatoes at another….” Little Booker cleaned the yards, carried water to men in the fields and took corn to the mill.

From such humble beginnings, Washington went on to become America’s most influential black leader at the turn of the 20th century. He worked to promote black businesses, help black farmers and secure financing for black schools. A well-known speaker, Washington advised governors, congressmen and U.S. presidents. (nps.gov/bowa)

Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts

One of the National Park Service’s most unusual sites, this green space for music, dance, theater and opera is a summertime hub of culture in the Washington, D.C. area. The 117-acre park occupies former Fairfax County farmland donated to the federal government in 1966 by philanthropist Catherine Filene Shouse, who also provided funds to build a performing arts center. The venue, located in Vienna, is operated in partnership with the non-profit Wolf Trap Foundation for the Performing Arts.

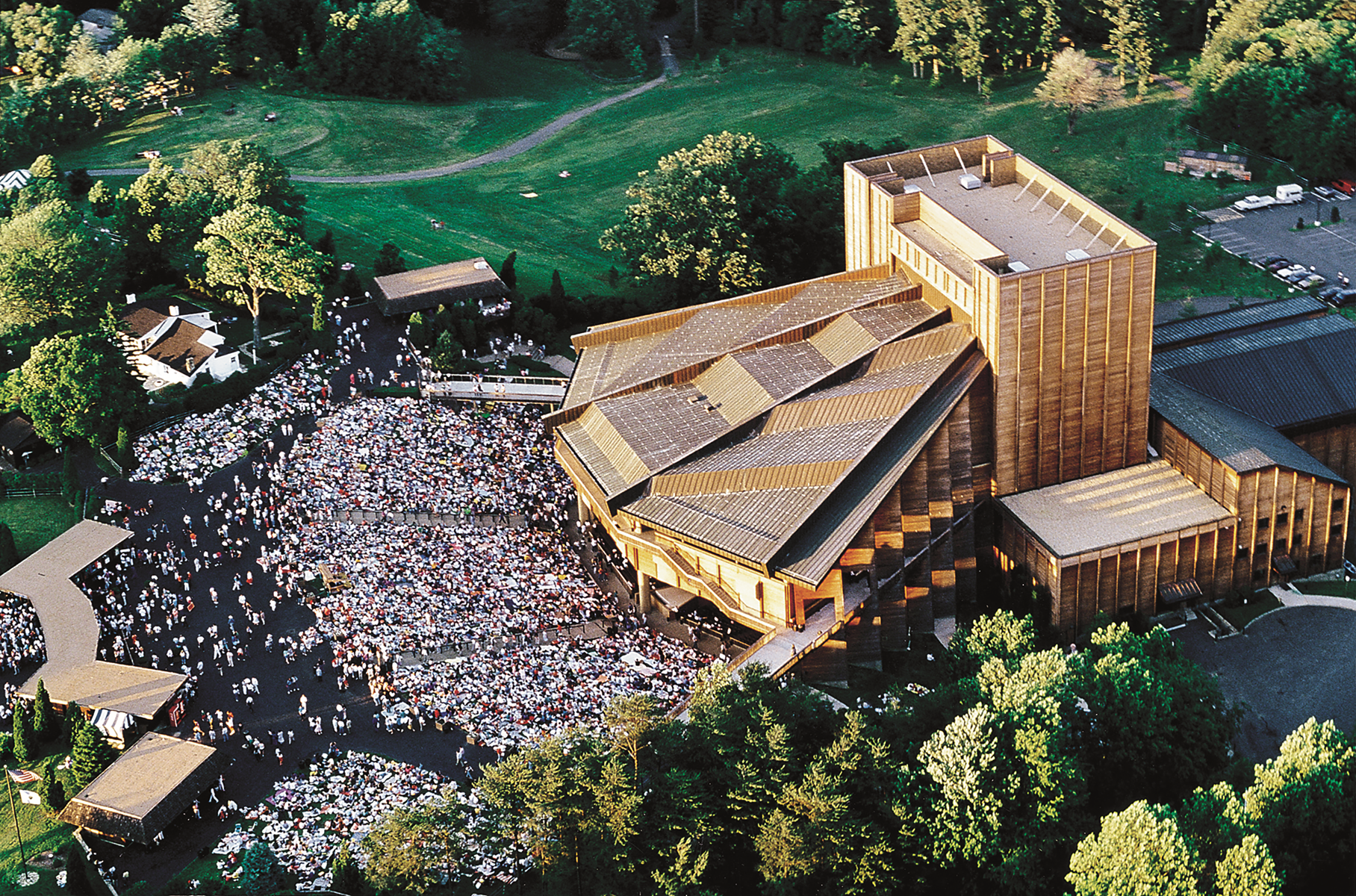

From May to September, the architecturally stunning Filene Center, an outdoor amphitheater built of Douglas fir and Southern yellow pine, presents all music genres, from country and pop to classical and opera. Wolf Trap is the summer home of the National Symphony Orchestra.

More than half the Filene Center’s 7,000 seats are under cover, and the lawn area f ills with concert-goers who bring blankets and picnic baskets. Wolf Trap also has a restaurant and concessions, and there are picnic tables throughout the park. Two hiking trails traverse the rolling woodlands.

The outdoor Children’s Theatre-in-the-Woods, across the meadow from the Filene Center, offers summer fare that ranges from music and dance to puppetry and storytelling. The Barns at Wolf Trap, not part of the national park, features a 382-seat indoor theater that presents opera in summer and a variety of musical performances from October to May. (wolftrap.org, nps.gov/wotr)

Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site

Restored to its 1930s appearance, the red-brick townhome of Maggie L. Walker in Richmond commemorates a leading black entrepreneur during the Jim Crow era. Long before women could vote and African Americans were afforded legal protections, Walker achieved success in business and finance as the first woman in the United States to charter and serve as president of a bank.

Ranger-led tours of this Virginia National Park in Richmond’s Jackson Ward neighborhood begin at the visitor center, located around the corner from Walker’s house; exhibits and a movie spotlight her achievements. Visitors also learn about Jackson Ward, a thriving black business community at the turn of the 20th century and today a historic district; many of the townhouses have cast-iron porches, the state’s richest display of ornamental ironwork.

From 1899 to the end of her life, Maggie Walker (1864-1934) was head of the Independent Order of St. Luke, a national fraternal organization dedicated to the financial and social advancement of African Americans. She opened St. Luke Penny Savings Bank in 1903 and two years later St. Luke Emporium, a department store that gave Richmond’s black community access to cheaper goods and provided employment for women. A revered civil rights figure, Walker pushed for educational opportunities for African American women and promoted the benefits of community engagement to youth in order to nurture the next generation of activists. (nps.gov/mawa)

by Randy Mink